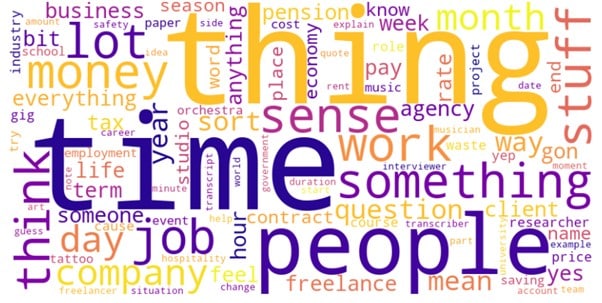

This article is written following the analysis of four semi-structured interviews with gig economy workers in the creative industries. Below is a word cloud of the most frequently used nouns from the interview transcripts – a quick visual introduction to the world of precarious creative work!

Introduction:

The gig economy, self-employment and, freelancing – a world often found in creative industries such as the visual arts. The instability of work is a reality that shapes the experiences of many artists pursuing their careers; struggling to navigate the complicated landscape of freelancing.

Named ‘The Creativity Hoax’ (Morgan and Nelligan, 2018), the gig economy has been criticised for its glamorisation in the media. The notion of ‘digital nomadism’ (Thompson, 2020) is an overexaggerated and glamourised depiction of the positives of work; such as a drastically improved work-life balance compared to the typical 9-5 lifestyle.

Whilst frequently seen in the media this is at odds with the reality for most freelancers. With little representation of the less glamorous gig economy work in creative industries, artists may find freelancing confusing, isolating, and lonely. There are positives to freelancing too, of course, however, more attention must be paid to the ever-looming shadow of uncertainty that darkens the gig economy’s door.

So how and why do artist’s do it?

Issue 1: Work-reward-cycle

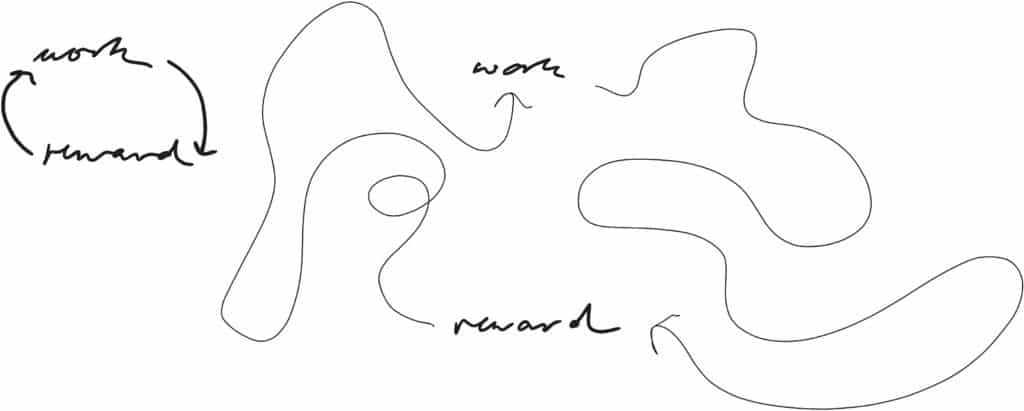

One frequently reported positive outcome of gig economy work is a short work-reward-cycle. The work-reward-cycle is a concept derived from ideas on well-being in the workplace such as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, where individuals need to feel a rewarding output from their input to be satisfied.

This piecemeal nature of gig economy work is at odds with the traditional 9-5 employment that is best understood in our society. The gig economy’s ‘bitty’ work was highlighted by interviewees. They mentioned a strong appreciation in being able to see a clear output to their work, which coincides well with piecemeal tasks. The work-reward-cycle is more convoluted and less binary in traditional employment types as there is less direct compensation for an individual’s work. For instance, the reward output for high input in traditional employment is split amongst a team or departments which reduces some individual responsibility and therefore, individual reward. Whereas, when freelancing, due to the shortened and individualised work-reward-cycle individuals may feel a greater sense of reward through recognition or financial compensation for their work.

Issue 2: Policy outsiders

The gig economy lacks social protections by government policies as seen in traditional employment (e.g., one employer and on a salaried contract). This affects different aspects of financial securities – from no sick pay to no employer pension contributions – gig economy workers are particularly vulnerable to financial insecurity.

Participants in the study reported the adoption of risk-averse behaviours. For instance, limiting bike rides and harsh realities like working online from a hospital bed due to economic dependence on the gig at hand. This shows that due to the pressure on the individual, gig economy workers may be less likely to put themselves in risky (but fun!) situations due to how vulnerable their income might be following an accident.

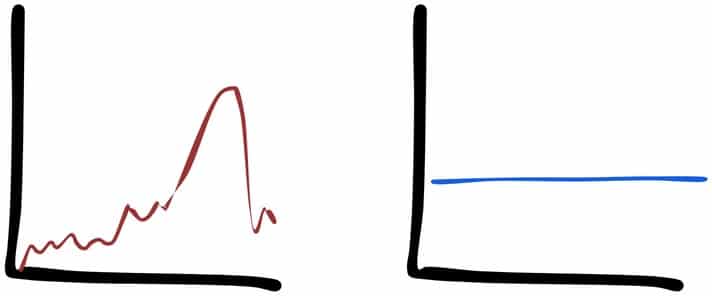

Issue 3: Slow seasons and ‘consumption smoothing’

Slow seasons are periods where there is less spending such as January lulls following an expensive Christmas time. These seasons are likely to lead to creatives seeing a significant drop in commissions and therefore, income for these months. Of course, slow seasons affect all businesses however freelancers are likely to feel this the most. Thus, consumption smoothing – the premise of balance between spending and saving in personal financial planning, may be a very helpful concept for freelancers to mitigate risk.

For freelancers, this is important because it is another huge area of financial planning that would typically be handled by the finance department in a traditional company structure. Rather, gig economy workers are required to cover all departments (e.g. legal, finances, sales, marketing etc.,) themselves. As well as consumption smoothing, some participants also stated that they struggled with knowing what is acceptable to charge clients and underselling their work, another business component which often requires expert market research from a dedicated department.

Struggles with financial planning are widespread in the gig economy and it is not surprising considering the lack of accessible financial education in the UK. The onus is on the freelancer to educate themselves, reducing stress by adding a degree of predictability through consumption smoothing (this is easier said than done!).

Issue 4: Coping mechanisms and blended employment

Many freelancers who grapple with financial instability in the creative industries are likely to engage with blended employment to make ends meet (pay rent). For example, picking up supplementary hospitality shifts or more permanent part-time jobs – one interviewee is determined to build a career as a performing musician but must supplement his income with regular teaching.

For some, this seems to be an effective financial solution. However, many individuals in the creative industries have had negative experiences in hospitality or 9-5 jobs; the interviewees reflected…

One participant explained how 9-5 employment had severely impacted their self-confidence as their ADHD and dyslexia were not understood by their employer. Rather, freelancing provided opportunities for them to schedule; accommodating their fluctuating energy levels and choosing work that plays to their strengths. Another participant spoke about their experiences of functional alcoholism in bar work such as feeling the need to drink to get through a shift. They then reflected how, contrastingly, freelancing increased individual responsibility and facilitated healthier lifestyle changes. The participant expanded further on this to say that their reputation and brand would be damaged if they were to be unreliable – therefore, introducing a business case to prioritise wellbeing!

Issue 5: Navigating the gig economy

Ultimately, the gig economy is here to stay in creative industries which means that it is important for research like this to continue. Research is an important driver to increase social security for freelancers through inclusive social policies, education, and support.

In discussion with the participants, it is clear that much work stress is a result of the increased pressure that comes from self-employment. For one, there is the need to navigate financial systems like filing for taxes. This is often a harsh learning curve for new freelancers and can result in fines – creating avoidable outgoings and adding to stress. Furthermore, the fear of potential sickness and not being able to work is another case of existing outside of the protections of standard employment policies.

Aside from policy change, freelancers may benefit from seeking financial literacy education to avoid fines and some income instability. There is also, as always, value in saving money when things are good to build up a ‘nest egg’ or to pool finances with artists, sharing a space for repairs and resources.

Moreover, it is important to remember that freelancing can be lonely, but this is a shared sentiment. Some participants mentioned that they had at times, really felt the mounting pressures of self-employment, and found talking therapies beneficial. There are low-cost therapy services available in most areas and emergency services available in times of crisis.

Conclusions:

There are many positives to freelance work. The shortened or more direct work-reward-cycle is a benefit as is the ability to choose their own work pattern and the jobs undertaken. On the other hand, policies are currently inadequate to effectively mitigate the issues facing freelancers due to a lack of research and understanding of this new form of work. The burden of finances on the freelancer is a heavy load to bear and requires much attention – this is likely to distract from the creative process, but still a necessity to create a living from their work.

Further research is needed to understand an intersectional impact of the gig economy i.e., the people who suffer from multiple levels of discrimination such as sexism and racism. These are those who will be most vulnerable because of gig economy work (Morgan and Nelligan, 2018) as they may be less likely to have safety nets such as generational wealth to act as a buffer against financial instability.

Author’s Note:

Observations based on research entailing four semi-structured qualitative interviews with participants in creative industries participating in gig economy work.

References:

Morgan, G., and Nelligan, M., 2018. The Creativity Hoax: Precarious Work in the Gig Economy. London: Anthem Press.

Thompson, B. V., 2020 “Digital nomadism: mobility, millennials and the future of work in the online gig economy.” In The Future of Creative Work. Cheltenham, UK Edward Elgar Publishing. pp.156-171

Josie Rodohan (she/her)

Current UAL student reading MSc Data Science and AI in Creative Industries. Josie is passionate about social research for social change – specialising in mixed methods, research ethics, data science, and accessibility in academia.